Rex was a bit off-colour this morning; not up at his usual 06:00. Hmmm …. Was he sickening for something. After a very quick breakfast, we set off at a brisk pace to the water bus terminal by the Groothoofd for a trip to Rotterdam. I acted as pace setter, and Rex cursed me; he still hadn't woken up.

We arrived in time, and shared the one and only seating area on the water bus with a large group of mixed American cyclists, all competitively trying to outdo each other in the decibel stakes. Rex's hearing aids were working overload to handle the incessant din. Our water bus ploughed up the Noord through much industrial land. Indeed, this waterway seemed to be a motorway of water.

The ticket conductor started his routine of selling and checking tickets, but must have decided to just give up after a short while to avoid the screeching emanations. I can't say I blame him. We never saw him after that; therefore, we had not bought tickets! Fortunately, all the Americans disembarked a few stops further on, all keen to spread their dawn chorus elsewhere.

At Kinderdijk, the Noord converged with the Lek, it became the Nieuwe Maas. Just behind the shipyards of Kinderdijk, hidden from view, a UNESCO World Heritage Park lay with 19 windmills dating from 18th century, plus a museum and working mill. Rex, Meryl and I had visited this charming park in 2015. Now we were on the Nieuwe Maas, huge docking complexes lined the banks, and large shipbuilding hangers squatted. Gigantic dredgers and salvage boats littered the quaysides, and the river was festooned with commercial traffic.

Life was bliss until the penultimate stop, where we were all unceremoniously told to disembark the water bus and catch the next one; the current craft was experiencing technical difficulties, and would have to return to harbour for repairs.

Fifteen minutes later a water bus on its way from Kinderdijk to Rotterdam stopped, and we all piled on. Of course we were soon approached by a female ticket conductor. We explained to the woman how the conductor on the previous boat had given up selling tickets.

"We'd like return tickets between Dordrecht and Rotterdam," I requested.

"Are you pensioners?" she asked, eyeing the two fossils in front of her up and down.

"Yes, we are." Amazingly we were entitled to reduced fares as a result.

The Rotterdam skyline as we approached resembled London's Docklands. Soon we were gliding under the Erasmusbrug, a cable-stayed bridge across the Nieuwe Maas, linking the northern and southern regions of Rotterdam. The iconic Erasmus Bridge was designed by Ben van Berkel and completed in 1996. The 802m bridge had a 139m asymmetrical pylon, earning the bridge its nickname "The Swan". The southern span of the bridge had an 89m bascule bridge for ships that could not pass under the bridge. This was the largest and heaviest bascule bridge in West Europe and had the largest panel of its type in the world.

Erasmusbrug |

In 1572 Rotterdam became involved in the Eighty Years' War between the Low Countries and Spain. A rebel army conquered the town of Den Briel and the Spanish forces led by general Boussu were chased away in a southerly direction. The rebels took advantage of the vacuum left behind and took Delfshaven. The next thing was a march on Rotterdam. The city fended off the attack, but a few days later the reassembled Spanish forces of Boussu were outside the city gates. The city was divided internally on whether to let them in or not. A compromise to let in only a few Spaniards led to a misunderstanding on which the Spaniards went on a rampage. The Spaniards consequently reconquered Delfshaven. Shortly thereafter the Spanish Forces were withdrawn to the south to fight yet another insurgency. The pro-Spanish Aldermen left with them. From that moment on Rotterdam was on the side of the rebellion. Those events, together with of the siege of Leiden two years later, led to the city government being confronted with the need for better protection. Under the leadership of City Secretary Van Oldenbarneveldt, the city was enlarged with new docks and fortifications.

Economically the next era was one of growth and prosperity. Trade and shipping flourished. Especially the trade with England, France, America and even Spain increased. The location was good, but also the political circumstances favoured Rotterdam. Delft kept its satellite port of Delfshaven in check because of short term interests, Schiedam was too thrifty to invest in a port and Amsterdam and Antwerp - both still on the Spanish side - were blocked by the fleet of the rebellious provinces. When Amsterdam chose the side of the rebellion a lot of trade went back there. The establishment of the Admiralty in Rotterdam (1586), a Chamber of the Dutch East Indies Company (1604) and the West Indies Company (1621), and of the Merchant Adventurers (1635) were proof of growing trade. In the 17th century, when the discovery of the sea route to the Indies gave an enormous impetus to Dutch commerce and shipping, Rotterdam expanded its harbours and accommodations along the Maas. Before the end of the century it was, after Amsterdam, the second merchant city of the country.

Rotterdam adjusted to the changed circumstances after the French occupation, which, from 1795 until the fall of Napoleon in 1815, halted most trade. The people of Rotterdam were vigorous and hard-working; trade and shipping flourished and new docks were built, feeding the rapid growth of the city. Transit trade grew more important, and between 1866 and 1872 the New Waterway was dug from Rotterdam to the North Sea to accommodate larger ocean-going vessels. In 1877 the city was connected with the southern Netherlands by a railroad crossing the Maas River. The simultaneous construction of a traffic bridge across the Maas opened that river's south bank, where large harbour facilities, extending westward, sprang up between 1892 and 1898. Between 1906 and 1930 Rotterdam's Waal Harbour was built; it became the largest dredged harbour in the world.

On 14th May 1940, during the Second World War, almost the inner city and the 17th century port were completely destroyed in a massive bombardment. Without any hesitation, the reconstruction programme was launched within two weeks of the war's end. Rotterdam made a radical break with the past and blazed a new trail, redefining the face of the city. Light, air, space and functional architecture were the watchwords. The original street plan was abandoned and the city centre was being connected by wide avenues. In 1954, the Lijnbaan Shopping Centre became the prototype for similar centres in Europe and America that allowed only pedestrian traffic. Rotterdam literally rose from its ashes and owed its contemporary image to the drive for innovation.

Suitably fortified, we strolled up Leuvehaven towards the maritime museum, our prime objective for the day. We had last visited here ten years earlier. A very large triangular harbour was stretched out on our right-hand side, which in turn contained a triangular island with quays on it. The small harbours on the island had names: Wijnhaven, Scheepmakershaven, Bierhaven, Rederijhaven and Leuvehaven, reflecting trade conducted on these wharves decades ago. This area formed part of the museum.

The layout of the museum had totally changed over the last ten years. Many Dutch museums undergo changes on an annual basis, the Fries Museum in Leeuwarden being another such museum. The Rotterdam Maritime Museum with one of the largest and most prominent maritime collections in the world illustrates six centuries of Dutch maritime history. The museum is located in the oldest and largest museum harbour in the Netherlands, where the port of Rotterdam once began. It was founded in 1873 by Prince Hendrik the Sailor. The Dutch are proud of their royal roots and are particularly grateful to Prince Hendrik for founding the key institute that stores, studies and presents Rotterdam's maritime heritage to the general public. The collection includes over one million objects from Dutch maritime history from the end of the 15th century through to today. This time span is something that the objects in other maritime museums in the country are unable to cover. Because of the size and quality of its collection, this museum is one of the best maritime museums in the world.

As soon as we entered the museum building, we were diverted to the Half Deck Offshore Experience. This primarily focussed on offshore energy, and the whole setup had been sponsored by a myriad of offshore energy companies and associates.

The experience was set up on a 'platform' in the middle of the sea. A 360-degree film projection stimulated the senses, and helped to impart a feeling of what it is like at sea with up to three kilometres of water below. The message was clearly put across that we cannot live without energy, and much of our energy from oil, gas and wind is extracted at sea - hence offshore. Working at sea is certainly not easy, and many clever systems have been developed to make safe the delivery or collection of goods and people when relative motions are varying by +/- 3m or more. Comprised of many individual interactive terminals and displays, the whole process of:

- how oil and gas fields are detected

- how the sea bed is often prepared for drilling with 'pancakes' of crushed rock, 30m diameter and 1m deep

- the erection of oil/gas and wind turbine platforms

- covering newly laid pipelines with crushed rock to protect them from anchors and fishing nets

- seabed repairs/operations, often by crews who live and work underwater five weeks at a time

- surface repairs/operations, surprisingly a lot now being handled by robots

- the enormous fleet of vessels that help to build and supply these platforms.

Available for the younger generations, several hands-on terminals allowed them to experience how drillers, crane operators, wind turbine specialists and helicopter pilots do their spectacular work at sea. They could attempt to guide a helicopter to the platform in a gale, hoist a container on board the platform when the waves are three meters high, find the most suitable location for a windmill at sea and other such challenges.

Aegir |

The Dutch company Heerema Marine Contractors (HMC) has been one of the world's market leaders for decades in the heavy lifting sector of the offshore industry. Their fleet includes the world's largest crane vessels, capable of installing oil and gas drilling rigs in the world's roughest seas and laying pipelines in very deep waters.

With a crane lifting capacity of 4,000 tons, the Aegir's primary purpose is serving the pipe-laying tower. A dynamic positioning system (DP) with seven propellers keeps the vessel accurately in place to let it carry out precision work. On top of that, the ship has remotely operated vehicles: robots controlled from the ship that can weld, cut and do other installation work on the ocean floor.

Both Rex and I were totally mesmerised by this experience, I could have spent hours there.

The next floor, was dedicated to how Rotterdam grew from a village to the largest port in Europe with its many docks stretching all the way out to the North Sea. This story, sponsored by Topsector Logistiek, was well presented and informative.

Another section on this floor outlined Rotterdam's involvement in the Slave Trade Triangle. It also had a display on how immigrants have passed through the port over the ages.

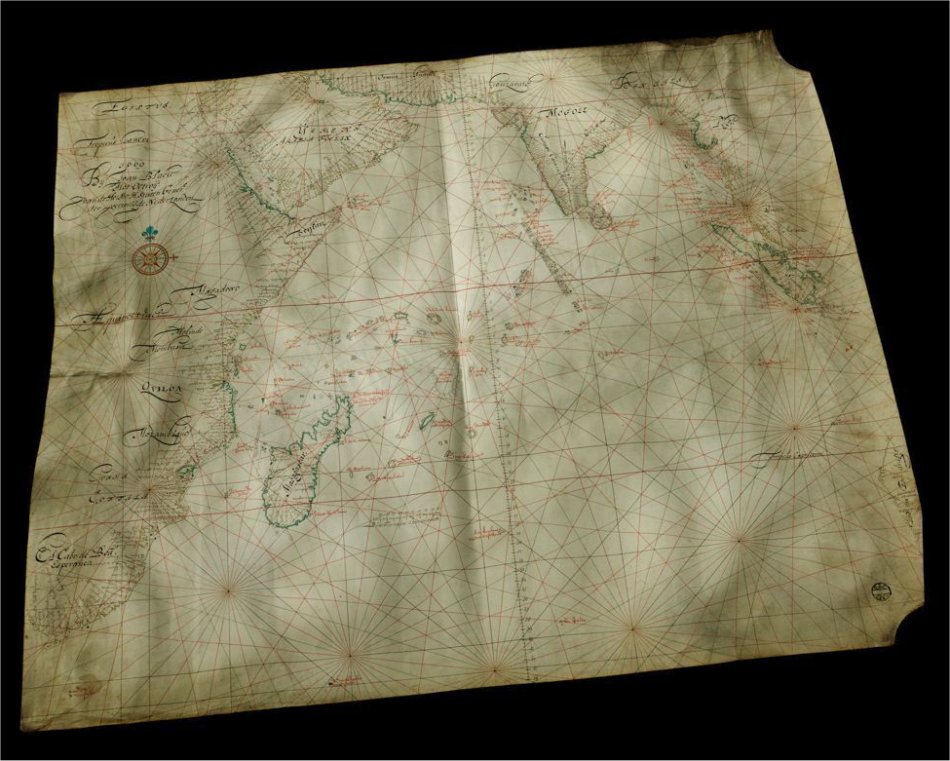

Of course Rotterdam was well connected with the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie - VOC), which traded across multiple colonies and countries from both the East and the West. The Dutch East India Company is sometimes considered to have been the world's first multinational corporation. Vitally important to mariners who went to trade in the East Indies were accurate charts. In the 17th century, Joan Blaeu was a publisher and printer as well as a cartographer.

Blaeu’s East India Company Map |

This nautical chart of the Indian Ocean, hand-drawn in 1669, shows Africa on the left, Arabia at the top and parts of Malaysia and the Indonesian archipelago on the right. It is what is known as an 'overzeiler' - an 'across-sailer' - that allowed courses to be plotted across the oceans. Until the 17th century, ships preferred to stick to the coastlines to avoid getting lost. That was a safe but pretty inefficient way of sailing and 'overzeilers' offered a faster alternative for those who dared to leave the coasts. The trick was to sail east-southeast from the Cape of Good Hope to the small island of Sa Paulo and then head for the Sunda Strait from there with the westerly wind in your sails. Anyone who missed Sa Paulo and sailed too far east ran the risk of ending up on the reefs and rocks of the Australian coast. One nice detail is the place names inscribed in black along the coast. The names of the bodies of water are in red. Unknown smaller islands were often given names that were invented by the passing skipper. When a cartographer adopted these names - followed by his fellow mapmakers - they became widely accepted. Internationally too: Australia went by the name Nova Hollandia (or New Holland) until deep in the 19th century, including in France and England, and Tasmania (named after Abel Tasman) got its name similarly.

Mataró Model |

This ship model is the only 15th century three-dimensional representation of a seaworthy cargo vessel that frequently sailed the seas in and out of Europe between 1350 and 1500, an important source of knowledge about late medieval shipbuilding. According to the story, the model takes its name from the chapel it came from in Mataró, a coastal town north of Barcelona. The model was based on a ship that was 18m long by 9m wide and had a draft of about 4m. A ship like this could carry about 100 tons of cargo.

Padmos |

When the Blijdorp ran aground on the west coast of Africa in 1733, it already had a lifespan of ten years behind it. That was about average, but the Padmos kept going for a strikingly long time, lasting for no less than 25 years. This model was built at about the same time as the two vessels themselves and represents both of them. That is why both names are given on the stern. The maker is not known. It might have been a former shipwright, or conversely an apprentice who had to learn how such a ship was put together. The near-perfect detailing suggests that it must have been someone associated with the shipyard, or at the very least someone who had extensive knowledge of this type of craft. Given its high quality and beauty, this model most likely stood as an ornament in a VOC boardroom.

In addition to the many model ships, this floor exhibited a lot of maritime art. Of note was a pen-and-ink drawing by the 17th century artist Willem van de Velde the Elder.

Pen-and-ink work by Willem van de Velde the Elder |

Leuvehaven |

Simson (crane) and Stadsgraanzuiger 19 (used to suck grain out of a large ship and deposit it into barges alongside - last one in the world) |

Beers in Scheffersplein |

In the evening, we headed into town for a meal, passing by the Stadhuis on the way. On the steps a young peoples' brass band were playing with great gusto. A large congregation of appreciative parents and onlookers were crammed on and around the Stadhuisplein to watch and listen.

We carried on to Scheffersplein where we settled for an Italian meal out in the intermittent sun. It was then that we noticed a long, continuous procession of groups of school children marching, chanting and shouting while some played musical instruments, each group displaying their group number on a banner at the group's front. The whole procession was heading in the direction of the Stadhuisplein.

I asked our waiter what all this commotion was about. Apparently, in Dordrecht, one week each year, all pupils in schools walk 5 km over that week. Today's section happened to feature music and singing throughout the town.

He did show us a pub where we would be able to watch the Euro 2024 football match between Scotland and Germany, but in the end, we followed it on the internet back on the boat. This was just as well, the weather had really closed in and the rain was hammering down. Scotland lost!